Violence in, violence out.

The 7th gen of consoles was a strange time for shooters. There were a shitton, is the main thing. FPS, TPS, and so very many Ps to S. Nearly 5 years into the 360’s life we were already extremely fatigued. Cover shooters were originally conceived as forward-moving platformers but eventually lost any sense of momentum in favor of attritional design, encouraging you to clear dozens of goons and push forward inch by inch, slowly navigating increasingly complex levels and enemy placements. As a result they became emblematic of “lazy” game design for the era. The slop genre of the late 00’s, if you will. Army of Two-core.

Meanwhile, in 2007, IO Interactive had been given a pile of Eidos money to make a gritty heist-gone-wrong game with all of the violence and none of the charm of a Coen Bros flick. Kane & Lynch was gonna be the bomb! Fully co-op, sick semi-cooperative multiplayer mode, cinematic levels, the whole 9. They poured cash into this thing, and to their credit the marketing was legitimately solid. Do you remember the Lynch trailer? I sure fucking do! That guitar motif fucking goes! Damn shame the game didn’t!

If there’s one thing you probably know about K&L, it’s that it was a middling game and a massive bomb. This is only half true; the game sold okay, it just didn’t reach its lofty expectations. Today its legacy barely pertains to the actual game at all. Instead it’s all about Eidos and Gamespot’s shifty marketing deals, ethics in games journalism (but like for real), and the courage of one Jeff Gerstmann who unknowingly gave up his job to tell the people what they needed to hear in his video review: “Kane & Lynch: Dead Men is an ugly, ugly game.”

That comment probably isn’t responsible for everything that followed. It can’t be, there are far too many cooks in the kitchen during the creation of any given AAA game. People need to move money, delegate labor, design, code, model, animate, test, advertise, repeat repeat repeat. They weren’t all repeating the mantra, hell, a lot of them probably didn’t even know it. But you can feel it, can’t you? The underlying darkness festering? Several people high up in that org chart, or possibly just Rasmus Poulsen but who knows, had one thought playing in their heads on repeat and printed it onto discs with Square Enix’s money:

“You think that was ugly? We’ll show you ugly.”

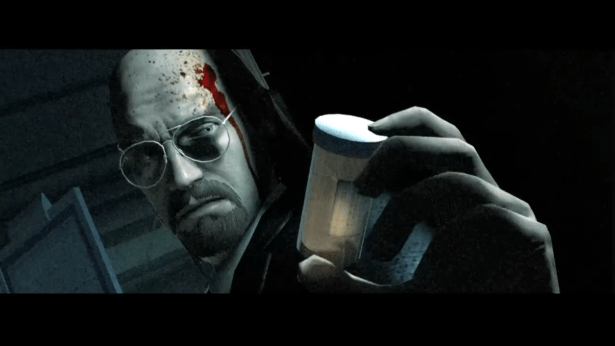

If there’s one thing you probably know about K&L2, it’s the existence of the torture sequence. The game opens on it, it involves a box cutter, it’s vile. I won’t dwell on that here. Instead I want to talk about the first chronological scene in the campaign proper, when Lynch welcomes Kane to Shanghai after three years of silence. Lynch tries to talk to the man he calls a friend. Kane is largely unresponsive, only commenting on their upcoming arms deal. Lynch faces the camera, lit by the city’s greenish bulbs. Kane faces away, shifting his eyes and stance often, staying out of the harsh lighting. One of these men is no longer who he was one game ago. The other very much is. In 48 hours the former man will be unmade, have everything taken from him, and be dragged away from his new life kicking and screaming by the latter, forced to regress to his prior state or die.

Lynch may be under-medicated and lack a moral compass, but Kane is a monster. For the first half of the game Lynch is constantly trying to get Kane to open up to him more than not at all. Their lack of communication only serves to make things worse, arguably the main reason why everything goes to shit in the first place, the flick of a pebble at the top of a mountain resulting in the game’s 3 hour avalanche. Kane doesn’t so much as offer to talk until after the torture scene, and he doesn’t do it out of a sudden realization or seeing the error of his ways. He does it because he needs someone to cover him, and no one else on God’s green earth would dare. When Lynch has a breakdown a little bit later, still nude and covered in bleeding cuts, he tells Kane that everything he touches turns to shit. Kane says they’ll discuss it later. This is a lie. If they ever do, we never hear it.

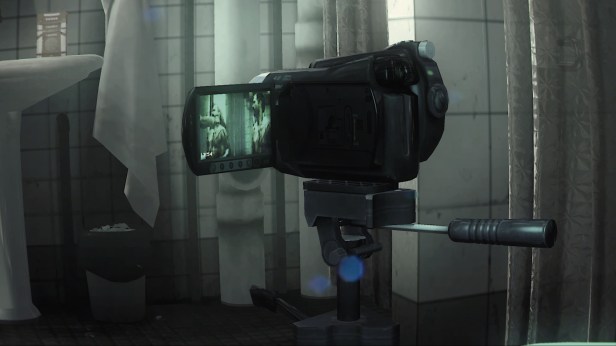

And who are “we”, exactly? The game’s presentation heavily leans on the concept of the camera being operated by a third character, someone constantly sprinting behind the duo, camera bobbing and bouncing all the while. “We” are not a character, but we are present, occasionally dodging fire in cutscenes, repositioning to get a better shot, and dropping the camera straight onto the asphalt when the player character is sufficiently shot. Look, it doesn’t make a ton of sense, especially considering that we get almost no footage of peaceful moments beyond 5 seconds of the boys getting a bite to eat before gunfire erupts. What it facilitates, however, is a very different story.

If there’s a second thing you probably know about K&L2, it’s that damn camera. This game is a Liveleak simulator. It feels like it could’ve been published in partnership with rotten.com. The constant wobble, the aggressive visual flares, fluids organic and otherwise flecking the lens, and that incredible auto-mosaic effect doing its best to shield the viewer from the game’s most gratuitous acts of violence. This combination gives me confidence in saying that this is one of the most jarring, violent games to ever be made with this kind of budget. We’re not talking Mortal Kombat cartoon shit, these are human beings depicted dying suddenly and horribly, often at your hand, and the lucky ones only get shot. It’s a gonzo documentary shot for an audience of internet perverts. Unfortunately these effects and their emotional impact comes at great cost; I can scarcely name another title that is so consistently capable of giving players motion sickness. Many folks I’ve spoken to about this game, and even more internet commentators, will tell you the game is only playable for them if their first input is going to the options menu and turning the screenshake off. It’s a shame, because I think the full experience only benefits from such an extreme level of disorientation.

On that subject, the game being recorded with a dogshit handicam means the audio is almost as hostile as the enemies. Gunfire is loud and constant, with breaks only serving to let the crowds’ shouts and ambient droning build before they’re once again drowned out with staccato streams of lead. When music kicks in it’s often subtle, in many cases diegetic. At one point during this last playthrough my wife compared hearing the gameplay muffled through the wall to a small child being set loose on a drumset, complete with screams. I get it.

In part because of this game’s oppressive presentation, the mechanics have been significantly simplified from the first game’s and its broader cover shooter contemporaries so that you can actually operate. No grenades or gear beyond your 2 weapon slots, only environmental throwables. No melee system, just a context sensitive human shield button that you’ll rarely use on enemies since getting shot at close range is often instantly lethal. No AI buddies to give orders to, just occasional NPCs that do their own thing in the early game, that is before Kane and Lynch finish alienating everyone around them. Aiming and shooting is a left trigger + right trigger job, typical of the era, and a deceptively generous helping of auto-aim smooths out what would otherwise be an incredibly difficult shooter to parse. At times it almost feels more like a light gun game than a 7th gen cover shooter. See mole, whack mole.

It’s the locations of this mole-whackery that makes K&L2 such a gripping ride for its feature length film runtime. With the exception of a particularly drab section in a warehouse yard immediately after the game’s visually brilliant mid-game, the locations you tear through always feel “real”. Cover is typically walls, benches, shipping containers, things you would reasonably expect to find in exactly the places you’d expect to find them. Populated areas end up looking like Hard Boiled as bullets start flying and the environment starts to buckle. Papers everywhere, broken furniture, cover fracturing with each impact before eventually breaking, camera reeling from the impact. The level design is legitimately excellent. My favorite sections are Xiu’s apartment complex, Shangsi’s office, the entire final airport chapter, and a fantastic gunfight in City Hamburger that does not go how you’d expect.

The level design is directly integrated with the plot progression. Your first taste of criminal activity is “just talking” with a mob member that’s overstepped a line, and it sees Lynch chasing his quarry through dingy alleys with uneven lighting. It’s exciting and energetic, one of the few times where you are the pursuer as opposed to the pursued, a typical video game power fantasy. By the end of our time with Kane and Lynch both men are desperate and exhausted, taking several smaller engagements to overcome their lack of numbers instead of extended firefights, using nearby airport equipment and workers to absorb shots meant for them without a second thought. The escalation is so extreme that the duo’s trip concludes with them hijacking a manned commercial airliner to flee the country, a trail of dead military and attack dogs in their wake, leaving your impossible cameraman for dead on the tarmac. They will doom everyone they meet, even the player, because no matter where they go everything they touch turns to shit. Violence in, violence out.

The folks who worked on the game have a lot of opinions about their work and what it means. A meditation on glorified violence in media, a subversion of 2000’s mechanical expectations, labeling what they made as an “anti-game”. I’m inclined to agree with most of that. Some also claim it’s postmodern, and it might just be, but I’m not even going to broach that here. What I want to contend, and I will dig my heels in on this, is that K&L2 is a more effective treatise on the vileness of video game violence than Spec Ops: The Line despite that game coming out two years later to broader critical acclaim. SpOps is a perfectly cromulent “war bad” game, but it falls victim to the same jingoistic dilemma all military media does, where any sufficiently well made work inevitably functions as propaganda. K&L2, by contrast, contains exactly zero aspirational figures, actions, or hell, even visuals. It’s violent and vile to a fault, and it wants you to hate that.

I imagine an immediate argument against this would be “well of course it makes players miserable if it plays badly”. This would be entirely fair were it not for the fact that Fragile Alliance, the game’s main multiplayer mode, smacks. In this mode’s new context of quick rounds, paranoia, and betrayals, it quickly becomes apparent how solid this game’s action is. Fast TtKs, snappy aim, taking teammates as human shields, excellent cover placement; everything sings when the campaign isn’t doing its dark work. There are folks who vouch for that mode to this day, running P2P lobbies on the PC version with other people who ‘member or dragging new friends in when the game goes on sale for a whole $1 again, and the reaction is almost always something to the tune of “wow, has there really been nothing else like this since?” The campaign’s grueling moment-to-moment gameplay, intensely negative emotional impact, and final gutpunch of refusing to tie itself up in a neat bow, instead opting to cut the player’s voyeuristic feed and go straight to credits? Few design decisions are ever accidental and that remains true here, both mechanically and thematically.

K&L2’s secret is that it was designed by people who knew exactly what players in 2010 wanted, and that meant they also knew exactly how to inflict the maximum amount of psychic damage upon them. It’s the least glamorized depiction of its content imaginable, to the point where the public and critics alike derided the game for that exact reason on release, fully missing that being repulsed meant it was working as intended. Gotta keep going. Gotta keep shooting. Oh, you don’t like how that feels? That makes your brain produce the bad chemical? Isn’t that interesting? Maybe ruminate on that a bit, eh gamers?

The most difficult part of making an anti-violent game is overcoming the fact that violent verbs, the most common ones in gaming as a whole, are typically implemented as fun toys for players to mess with. Modern openly anti-violent games are often content to just take them away, to be smugly critical from a distance, to tut-tut those who make and enjoy “those” games, only to replace their own verbs with sweet cozy nothings. Other attempts at violent anti-games like the No More Heroes series and The Last of Us 2 get closer, but are let down by inconsistent writing and game design that is far more concerned with making the player feel powerful in their combat arenas than supporting the narrative. K&L2’s campaign gets the closest I’ve ever seen to being a AAA game entirely about grappling with violence, where your only means of interacting is violence, that still manages to make a coherent argument against said violence. It is self-critical, intensely so, and it respects the player’s intelligence enough to present itself as such without having Lynch face the camera and tell the player how much he regrets his naughty behavior. Maybe that respect wasn’t fully warranted in 2010, but we should all aspire to such a level of confidence in ourselves and our audiences.

Square Enix got the K&L rights from IO in the divorce. If we were going to get another game it probably would’ve happened already. The portable tactics game got canned, as well as the planned film adaptation, which is probably a net positive. The “franchise”, as it was pitched to shareholders and the public, died here. It’s all the more astounding, then, that IO took the opportunity for a sequel and decided to make a game so subversive, so uncompromising, so fully committed to its core conceit consequences be damned, that 15 years later its intended audience is only now starting to “get it”.