Late Night With the Devil

I’ll be up front: you’re not going to play another game like INDIKA this year. Sure there will be other third person adventure games largely rooted in story-related set pieces and light puzzle mechanics to break the walking simulator aspects that will pop up on your catered game store page of choice, but they’re not going to be like INDIKA.

Set in the outskirts of Russia in the 19th century, you play as Indika, a monastery nun outcast by her compatriots for past infractions we learn later in the game, and also her wild lapses around others based on her internal struggle with a voice inside her head, the voice of the Devil. Indika is given a letter to provide to another church leader that calls her to leave the monestary and traverse across towns, but is sent on an unexpected adventure of self-discovery and sobering questions regarding the morality of religion, as well as the balance of free will and heavenly expectations.

INDIKA starts with an over-the-shoulder perspective going through daily chores, done almost as a penalty than a necessity, giving the player a front row seat in the uselessness and unnecessary nature of these tasks. Taking a basket of potatoes from one part of the village to another with no thanks, having to walk back and forth several meters to fill a barrel with water from a well, using each keystroke to begrudgingly turn the crank, only to result in no satisfaction for Indika or the player. No respect given, but respect is expected to be earned.

Past experiences where Indika has inadvertently put herself in this scenario are peppered in this slowly-paced intro, highlighting some real off-beat, slightly confusing, but chuckle-inducing cutscenes where you get a front row view of what Indika is having to deal with while maintaining her stoic status. The pixelated, 16-bit flashback scenes and UI are pleasant to look at although initially a little confusing on a design scale as the game’s more realistic presentation everywhere else doesn’t allude to these whimsical diatribes. Is this Indika’s representation of a more fantastical world before succumbing to the lowly drudgery of an emotionless standard?

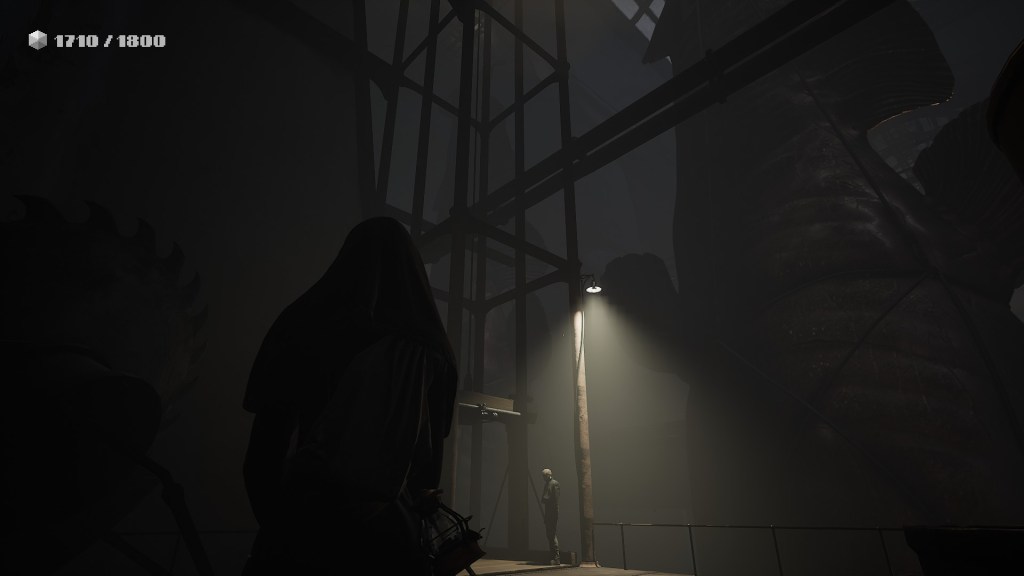

Indika can perform godly tasks, such as lighting lamps draped with icons of Christ and praying for the recently deceased, giving Indika “points.” These points are constantly displayed in the top left corner and used to “level up” with skills such as Guilt and Repentance, which generate even more points for your good deeds. It’s a tongue-in-cheek way to show that people will perform works for their religion for internal gratification and the feeling that they’re reaching a higher point in their beliefs. But the game will flat out tell you they’re worth nothing. Karl Marx will agree as well.

Once she is given the letter to present to another church leader, the world opens up to a blustery winter landscape and our adventure truly begins. Indika is soon attached to Ilya, a prison escapee who is looking for divine intervention to repair his frostbitten, mangled arm. Ilya takes Indika hostage and forces her to escape with him while she pilots a steam-powered bicycle in what has to be the funniest chase sequence I’ve seen in years. Monty Python aficionados would be proud at the ridiculousness and pure comedy of this moment and gets you in a great set of laughs in between the bleakness of the surrounding travel.

From that point on INDIKA puts the realizations and hypocrisies of specific parts of religious happenings to light, and in turn, puts Indika in a state of teetering belief and splitting guilt. Fighting the other side of her arguments literally splits her psyche in two, retreating to muttered prayers to temporarily fix her tempted ways. INDIKA uses this mental anguish to introduce small puzzles while your internal Devil insults your attempts to ground yourself. It’s a very cool mechanic that sadly isn’t used often, but is memorable for when it did show up.

INDIKA spends most of its time outside of cutscenes and plot advancing breaking the tension with smaller puzzles. Puzzles range from building structures, to navigation, to…uh, maneuvering past a massive dog-wolf being looking to make you a human chew toy? None of the puzzles are too hard but are satisfying enough to finish and provide a nice break in the walking simulator path the game takes when not putting the square peg in front of the circle slot. It’s worth noting that INDIKA’s use of camera and perceived angles, especially as truths are revealed to Indika and the world before her begins to be seen in a different light in the third act, are some of the smartest I’ve witnessed in a long time. The use of different perspectives on a point of view level left my mouth agape as it expressed exactly what it meant without even saying a word.

The story clocks in at a tight 3-4 hours and never feels like it overstays its welcome. There really isn’t much in terms of replayability, not that you really need it for this; it’s telling its story and you’re here to indulge. I did run into some minor slowdown in the more populated areas that really did not enjoy motion blur, even on turned-down graphical settings. I was really jazzed to play INDIKA in its natural Russian language, but text used within the world is not subtitled nor is the small talk from other characters, so I moved back to English to avoid missing anything. The English voice actors did a damn fine job in and of themselves, so I have no complaints other than missing out on some desired authenticity.

INDIKA is a weird game to score because it is, like said above, like nothing you’ve played before. It’s proudly weird but grounded in its reasons to be, laugh-out-loud funny and despairingly somber on the flip of a coin, and just long enough to get its deeply rooted point simultaneously into your heart and your brain. Odd Meter and 11bit studios embrace a topic often left alone, but the glory of Video Games is that you can take concepts as silly, in-depth, depressing, enlightening, eye-opening, and soul-crushing as the ones provided in INDIKA, and with enough heart and tenacity, create a near masterpiece.