Take a look, it’s in a book

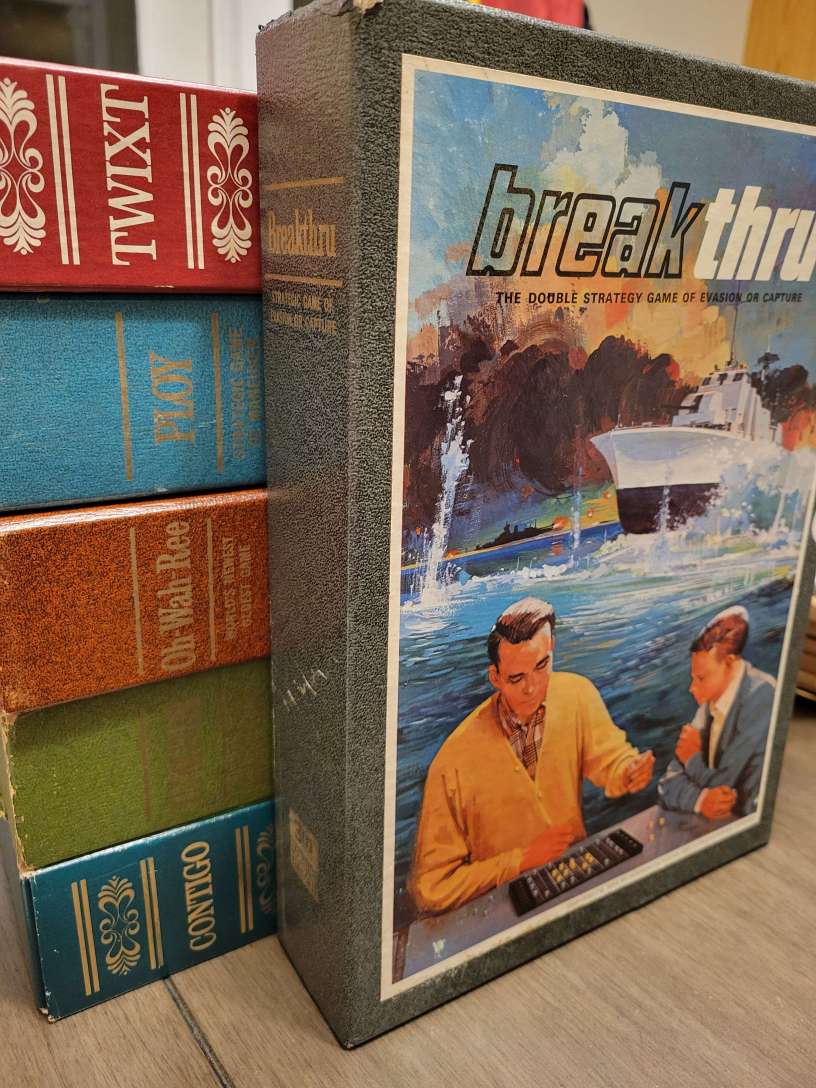

There was a time back in the 60s and 70s when some of the best designers in the world were publishing with the Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing company. 3M was, in a move that’s difficult to follow even in hindsight, printing high production games made for display on a bookshelf. They were “handsome” (per their marketing copy), wildly varied, and occasionally brilliant. This is where games like Sid Sackson’s Acquire and Bazaar got their start, as well as fan favorites like Feudal; 3M had a higher hit rate than many modern publishers!

This article’s focus is on 3M’s original abstract games. This means I won’t be including their boxed versions of Backgammon/Chess/Go, and I’m also ignoring Feudal despite its Chess ties because it’s a full on multiplayer dudes-on-a-map experience with fancy miniatures and terrain and that just seems out of spirit, even if it’s a good’un. I’m talking the abstract games that didn’t exist before these printings even if their ancestral line is plain to see. This was a fascinating dive to take, whether the games were good or not. Speaking of…

6: Contigo

Contigo plays like a contractual obligation. The production is notably worse for starters, from the flimsy box to the lousy pieces, but that’s far from the main issue here. What truly holds Contigo back are its two halves not feeling remotely connected. The movement of the pawns being dictated by a pseudo-Mancala just doesn’t make for interesting decisions. Instead you end up with the same endgame plan as regular-ass Connect 4: create a board state where you can win two ways. That’s it. It lacks the same attention to tuning and development of the rest of this set, and given that it was the last of these to be produced as 3M was winding their game division down I suspect that may have been the case.

5: Ploy

I was particularly excited for Ploy going into this. It was presented as A Game of the Future, like some sort of “Space Chess” where you could almost imagine the pieces as ships, making sneaky moves unlike any other abstract that came before. And in a way it kind of delivers on that premise. Unfortunately none of those moves are interesting.

All of the pieces in Ploy can only move in straight lines for relatively short distances, no jumps or changeups mid-path. A turn consists of either moving a piece or turning it so it can move differently in the future. This is not particularly exciting and there’s no twist to this paragraph, you just try to trade your opponent’s more valuable pieces and slowly bleed them dry. What you end up with is less “Future Chess” and more “Boring Chess”. So boring, in fact, that when I was working on the final ranking for this article I literally forgot Ploy existed and had to add it in late. It’s better than Contigo by merit of not being miserable, but only just.

4: Jumpin

Did you know Chinese Checkers isn’t Chinese? It’s German! Neither is Jumpin, which makes the orientalist wallpaper on this one uncomfortable no matter how much I’m reminded that the 60’s were a different time. The game is also uncomfortably mid!

This game is essentially Chinese Checkers for 2. The early and lategame is a bit samey, with the latter in particular running longer than I’d like as you try to fill your opponent’s starting area with pawns. That said, there is something to the midgame of constant back and forth, blocking, and multi-jumps launching your pieces across the board and past the goal line. If it could be distilled down further, possibly by shortening the board and making a few other tweaks, this could really be something. As it stands this is the only game that very much feels like an artifact of a time I’d rather not dwell on.

3: Twixt

It’s probably not a coincidence that the top 3 games on this list are all iterations on classic games by noted ludo-luminary Alex Randolph. Twixt is a riff on certified 1942 banger Hex, a game so known that you can play it in Nintendo’s Clubhouse Games and then look up forum posts where upset players ask how to win if they don’t go first. Hex is a solid abstract, and so is Twixt! It just isn’t quite different enough to warrant a recommendation over its predecessor.

So how does it differ? Well, you can only link pieces that are exactly as far away from each other as a knight’s move in Chess. And you link the pegs up with lil bridges, that’s neat! Seriously, I struggle to identify too many ways in which this takes Hex‘s foundation and actually changes it. The gameplay here is fine, don’t get me wrong, but the fiddly little plastic bits have me reaching for Hex itself, other “get from side to side” games like Quoridor, or some of its more notably different cousins like the recently released Garden Guests.

2: Breakthru

I will readily admit that I’m far from a Hnefatafl expert. Tafl games, AKA “Viking Chess”, are a compelling abstract category that sees far fewer iterations in the modern era than many similarly ancient games. If you’re unfamiliar with these they’re fairly easy to summarize: one player has a large force of identical pieces that move like Chess Rooks surrounding the middle of the board. The other starts in the center with fewer pieces and a King. Their goal is to get their king off the board while the opponent tries to prevent this. In vanilla Hnefatafl this means surrounding the King on all sides before it can get a corner of the board. Breakthru follows neither of these conventions, and these changes make it the extra-crispy to Tafl’s original recipe.

Breakthru is ostensibly set as a naval battle. As such, any border space is a victory for the king (flagship) as it sails into the sunset. However, Breakthru adds an additional element to piece capture: a dedicated move for it, in fact! A single diagonal scoot will take down an opponent’s piece and further emphasize the uneven piece counts. You can move more each turn than you can capture, both in distance and with two pieces as opposed to one, so every single decision to capture feels like a turning point. All of this, made even more interesting by a player-chosen board setup instead of preset unit placement, makes this a genuinely compelling iteration for the Tafl-curious that feels like it has far more to it than meets the eye.

1: Oh-Wah-Ree

Mancala and I have never exactly been besties. I like it fine, don’t get me wrong, but my ability to chain moves in or create a long term plan in that game has always been flimsy at best. I did not expect Oh-Wah-Ree (OWR from here because I am not spelling that out phonetically for the rest of this entry) to be much more than a modified Mancala. I mean it is that, but it also isn’t. I’ll elaborate.

The base ruleset of OWR is mostly the same. Move stones counter-clockwise from pit to pit, dropping one in each, and possibly score some if you land 2 or 3 in a pit belonging to your opponent. This can chain if multiple low-stone count pits are nearby, which is always fun and replaces the “take another turn” mechanism Mancala is built around. So far this is different, but not massively so. Then we flipped to the page of rules that turn the game into “Grand” OWR, and what followed was one of the most fascinating abstracts I’ve played in quite some time.

The Grand ruleset adds a function to the marbles that mark which pits belong to which player. Now when you capture a set of stones from an opponent’s pit, you also take possession of the pit itself. This means you have another pit to play from and one less to score from, and this is potentially in the middle of what was once their side of the board. The win condition also changes to reflect the importance of board control: the winner is the player with the most controlled pits, with stones only serving as a tiebreaker.

I know this reads dry. “That’s just Mancala with like two extra rules!”, I hear you grumble. Yes it is! And it rocks, figuratively and literally. Grand Oh-Wah-Ree gives Mancala multiple win conditions, and that decision space is the best I’ve seen in any game with pit-dropping at its core. How hard do you push for small captures, knowing that you’ll lose a tiebreaker if it comes to that? Can you set up a chain without breaking the streak of pits you don’t own? How do you get out of having your own pits reduced and with them your options to play from? How do you time all of the above over the course of the game? These competing tensions bring layers to the game of Mancala I’ve never quite seen or felt before. I feel like I finally get it; I finally see why this ancient and absorbing game of strategy has been played by Afro-Asian peoples for 3500 years, it just took another two rules for me to get there. Thanks 3M!

I believe an honorable mention should go to Evade, the one abstract “Gamette” from the 3M line. There are shades of Breakthru in the game, but it’s a very quick paced game. It is not complex and I’ve found it to be a great way to introduce a 5-6 year old to abstract gaming and kill a little time while we wait for their parent to pick them up from my wife’s preschool. When I bring it into classrooms, up through middle school, through playing multiple games with the same kids, everyone starts to anticipate how their opponent thinks. At that time, it has some surprising staying power.

LikeLiked by 1 person